With chief engineers earning upwards of £175,000 a year, and drivers earning up to $100 million dollars per year, it’s fair to say Formula One is a bank of monetary opportunity. But to get there, Willem Toet had to fight through numerous barriers.

Growing up in Australia with a widowed mother and abusive father figure Willem left home at sixteen. With no internship or networking opportunities, Willem advanced himself through the University of Melbourne, Australian Formula 2 and Australian Formula Ford, into the world’s most prestigious engineering roles at Formula One.

‘I had a weird and really tough early life. My dad died when I was six. My mum had five kids and one on the way and we had a period of no money. Then living off a widow’s pension, which pays two tenths of stuff all.’

Mentioning his mum’s new boyfriend and consequential father figure Willem became more serious.

‘He was a nasty piece of work and used to beat us all up’ and the ‘beatings got so bad to where I was literally bleeding on the seats at school, and then the school called the police, and the police did nothing because he had mates in the police force. Anyway…’

Willem had an ability to abruptly round off a topic, flitting to the next when we entered the depths of the story. When he was done, we were done, and I liked that directness about him.

With an unstable early life, I wondered how Willem had managed to make the most of bad situations, and how he found himself in one of the most heavily funded sports in the world. After leaving home, Willem found himself a job and enrolled himself at the University of Melbourne with a scholarship.

‘I got my very first girlfriend pregnant at university,’ he admitted. ‘I had to take a year out; her parents disowned her.’

A tricky situation for anyone, especially for Willem as his life was stabilising. Fearing the implications of his upbringing and how he could treat his child, Willem was scared.

‘I was eighteen, very aggressive, and I thought, this is not being passed to the next generation. I’m not going to be that aggressive dad that beats their kids up. Not going to happen. And maybe it wouldn’t have happened, but I was scared. I was really scared.’

The pair ultimately decided to put the baby up for adoption, with Willem meeting his son later in life.

‘Going to university, I needed wheels. I got wheels and that got me into cars. […] I got a job, night shifts at a garage and I worked [Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights]. […] People would come in sometimes with broken cars that weren’t reliable back then. I burnt my face [fixing a car] once. There are two types of radiator caps on old fashioned cars, long reach and short reach. Someone had put a long reach cap into a short reach radiator, [and long story short] my whole face came up in blisters.’

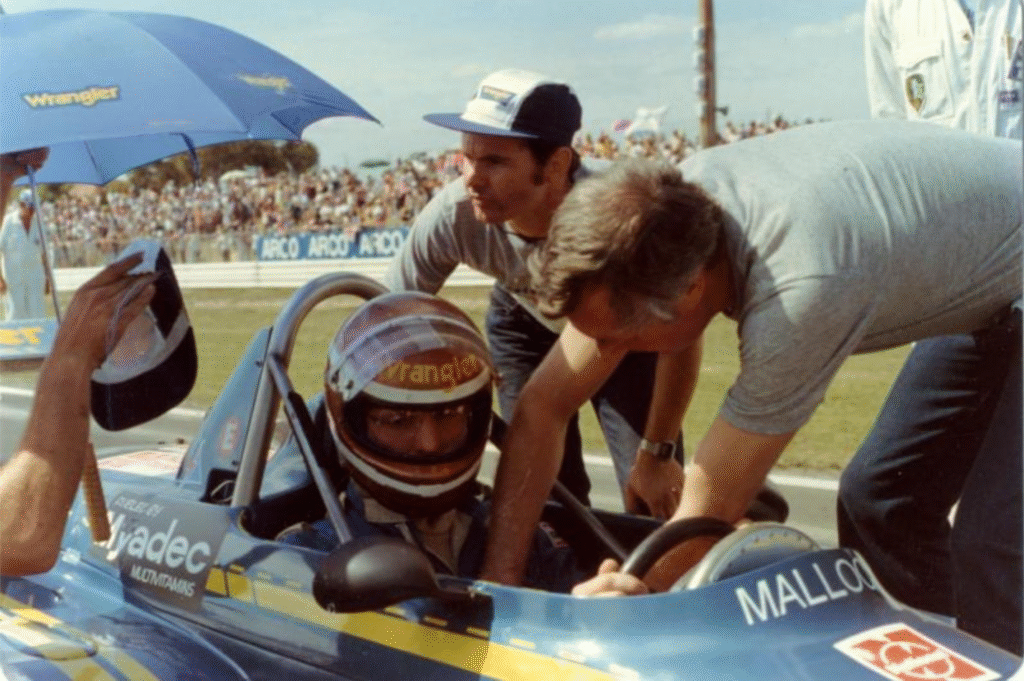

Regardless of injuries, Willem decided that engineering was the carer for him. Later attending a driving school, Willem met his first wife, Sarah. ‘She’s just better than me,’ Willem recalled as she won the school race. Willem would prepare the cars for Sarah, and then she’d race.

‘We only lasted two years once we got married. […] Sometimes you pick the wrong person, it doesn’t work,’ he said. ‘I’d fallen in love with her, but that had also led me to motorsport.’

(Image credited to Atlantics Calder, 1981, Ray Mallock and Willem Toet)

Speaking like a familiar father figure, checking that I was voice recording, he leapt into another story.

‘It took me two years before I was even the least bit interested in looking at another woman. It was like I had to mourn.’ Remaining in Australia until the divorce was settled, Willem moved to the UK at twenty-nine, which is when he met his wife Sue.

‘I saw Sue at Le Mans,’ a dream for any motorsport fan. ‘It was like wow. […] We were standing around and then one of the guys said, ‘look at that lovely woman’ and I said she wasn’t my type. Then I spotted Sue. It was like magic…’

After speaking to Sue, and asking for her number, she eventually rang Willem three weeks later. ‘I reckon she had to get rid of a boyfriend. She swears, no, she just wanted to make me wait a bit.’ The cheeky Aussie accent added to the charm of the story.

Talking about his eagerness to date Sue and her delayed responses, Willem quickly wrapped up the story with an abrupt ‘anyway, we’ve been together ever since,’ sealed with a smug smile.

The cheerfulness of Willem was what struck me the most. From a tough childhood and turbulent young adult life, Willem astounded me with his positivity and relentless nature.

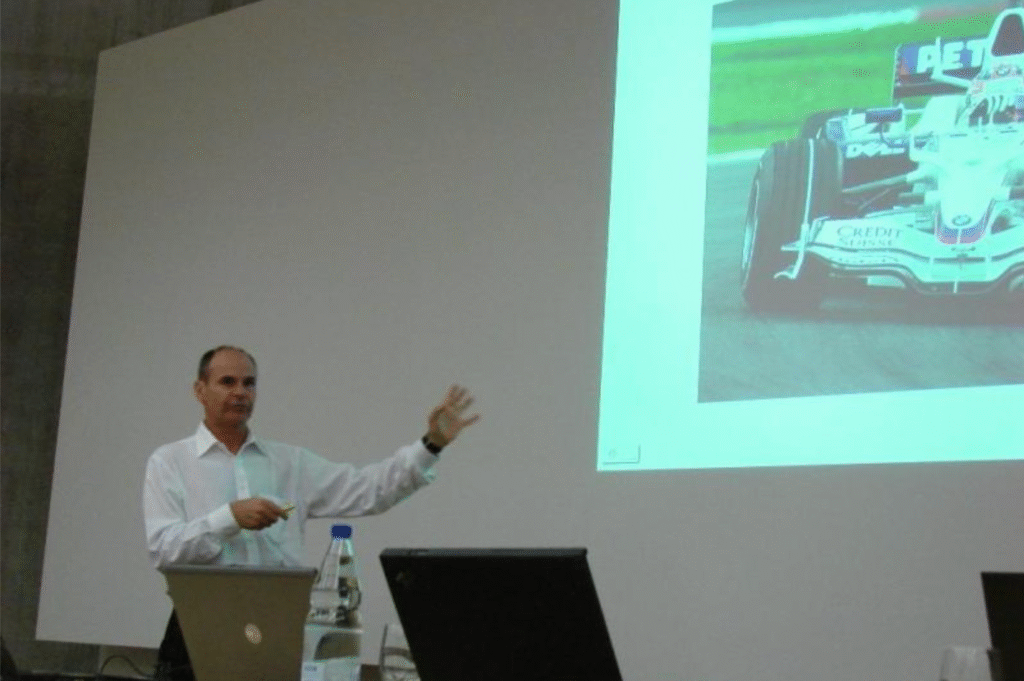

Spending his early years dodging his abusive father figure, fearing how this would affect him and making ends meet with garage pay checks to now, an ex-Head of Aerodynamics in a Formula One team and a university lecturer supporting the next generation. Throughout his career Willem has worked in senior roles at Benetton, Reynard, Ferrari, BAR Honda, BMW Sauber and is now a professor at the University of Bolton.

I’d originally contacted Willem to ask him about his observations of sexism in the motorsport industry and his thoughts on how to combat such attitudes.

‘What’s of interest to a boss is what’s in the brain,’ stated Willem. He didn’t care about nationality, race, or gender. He wanted a diverse team with diverse ideas, who came with a range of educational backgrounds and personalities. To solve difficult problems a team needs a range of perspectives, so if a team wants to be the best, you shouldn’t ‘ignore 50% of the best engineering brains in the business just because they’re not in a body of the standard shape.’

Now in his early seventies, Willem experienced a very different workplace than we see today. Mentioning sexism and racism in the industry, Willem expressed his distaste for the narrow-mindedness of one of his past teams. ‘I wanted the diversity that I’d seen because it can be a monotonous education, one style,’ which can be incredibly unhelpful if ‘you’ve got really difficult problems to solve.’

(Image credited to Willem’s LinkedIn, Willem Toet giving a talk at Sauber, 2015-2018)

Referencing the differences in nationality and culture, Willem mentioned how one of his previous female colleagues faced a tougher work environment due to being a confident woman. ‘I knew ‘Jayne’ would struggle in the race team at Sauber because she is direct and bold and female. They’re not going to like that she’s a female telling them what to do.’ Working at Sauber from 2008 to 2013, ‘Jayne’ moved to a role at Mercedes Formula One Team where she has worked since. “Jayne’ would’ve been more than capable of that job, but I wouldn’t give it to her because the team would crucify her.’

Despite all odds, Willem found his way to success in a saturated industry of dedicated engineers, overcoming the odds stacked against him as a child, proving that perseverance and hard work pay off, even if you play the long game. Not only was Willem willing to dedicate some time to speak to me about women in the motorsport industry, but he was also willing to spend hours doing so. We spoke for over two hours, discussing his life, career and how he supported up-and-coming female engineers.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *